6. Three Washerwomen

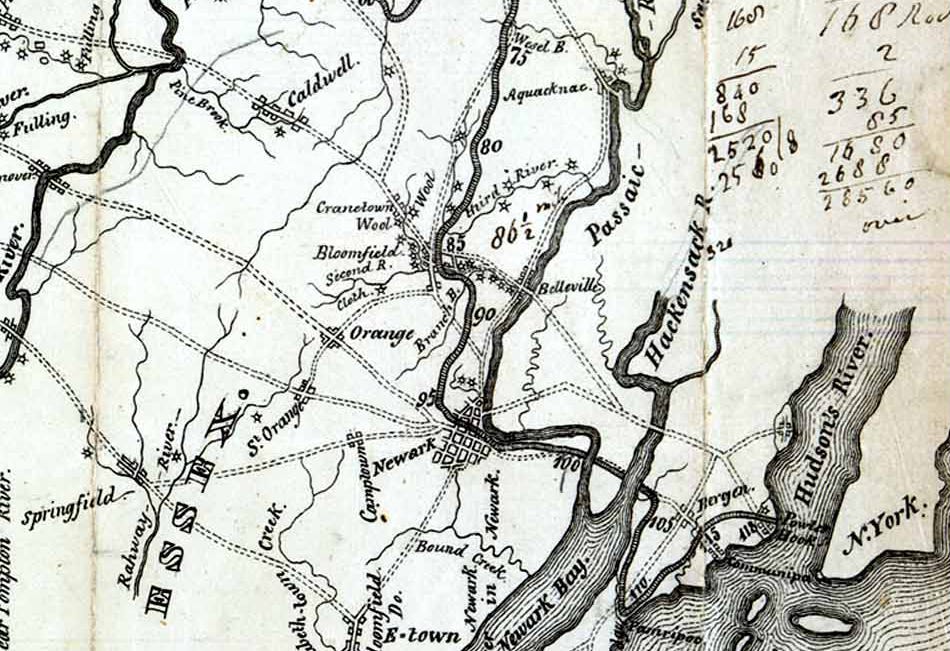

Once upon a time, long before New Ark’s first flood, there were retaining walls along the two main riverstreams that flowed across it and into the rising Passaic. Called the Watsessing and Yantecaw rivers by those who lived there before, these tributaries were polluted, bound to commerce and exploitation, and renamed the Second and Third rivers. They were sources of food, then open sewers, then hindrances to real-estate development, then boosters of property values, then public trash receptacles, then protectorates of the administrative state and its environmental protection bureaucracy, and then everything changed. The walls decayed and crumbled into their streams, creating new and unexpected bodies of water, but also cutting off the free flow of fresh water through the city, and only Prince Appall undertook to clear the fresh waterways for the free use of the people, for which he was applauded and excused much of his ill treatment of them. Still, though the people had managed to maintain their own pipes and plumbing, the public waterworks—reservoirs, sewers, treatment facilities, storage—remained as they had been: inconsistent and unreliable in function and quality since before the North Atlantic wars. Water was Appall’s only valuable public work, and his death by it must finally judge that work a failure.

But the rivers did flow, unhindered but for the occasional unlicensed homemade hydroelectric generator or bootleg grain mill, and so Rytius took a long way home through Soverel Park, to listen to the rush of the Watsessing there, and to check whether any wild fowl had yet returned, though he had brought nothing to feed them. The sky scattered crumbs of ice that melted upon contact with earth or anything therefrom, and the air hung on the knife’s edge of actual cold, as though at any moment it might suddenly slice through your quickly donned scarf, and into your inadequately covered breast beneath to have caught you slipping. While the river walls had crumbled, the footbridges remained, and a half-dozen fishermen crowded Rytius’s favorite, eager for a larger catch, hoping that the carp and bass would be agitated and disoriented by the rise in the waters. Three well-insulated washerwomen—they must have been in business, because it is hard to imagine a wife or concubine going out in such weather—were working in the stream, two on the eastern bank and one further up on the western bank, and they used the remain of the walls as shelves for their woven baskets of laundry, which this morning would not drain half dry during the work, but were taking an extended rinse from the freezing rain.

The first washerwoman was vexed behind this, because she had brought two extra-large baskets of clothes to wash on the eastern bank of the river, hoping to finish more work and receive more revenue that much more quickly, because the river’s speed and depth would make the washing easier and more efficient, but she did not carry her thoughts to their conclusion. She had neither plastic sheeting nor oilcloth, and so the rain that made the river more powerful would also make her trip back more burdensome, because the water would soak steady through her laundry. Though light enough to work in—and she was clothed in full-body waxens and leathers—the steady drizzle accumulated within the fibers of her wash, and it was easy to imagine, were the temperature to drop just a bit, that the top layer of the laundry might freeze over and build up an icy surface, adding that much more weight. Rytius watched her quickly finish rinsing the last sheet of a set of bed linens on her portable folding rack, wring it out as best she could, pack it into one of her two gigantic baskets, fold her rack and pack it onto her back, and then undertake quite a bleak struggle to shoulder the beam on which her overweight baskets hung, one on each end. It was a sight to see, and the fishermen mocked her gently. “You got to get it square,” “I don’t know what you were thinking coming out here this morning,” “You ain’t got enough back to put in it,” and talking about how it weighed near as much as she did. She could hardly get her footing there along the bank of the river, and she slipped and fell backward, whereupon each basket opened and some of the fresh wash of one fell into the mud and some of that of the other fell into the water and began to flow downstream. The fishermen fell to laughter and exhortations to hurry up and go get it, and Rytius chuckled and wondered what she would do and how she would do it. She yelped wordlessly and twisted out from under the beam and quickly dragged it a bit back up the riverbank, left the mudded items, and chased the ones in the water. A flotilla of undergarments—socks, drawers and T-shirts—moved quickly downstream, but also quite directly across, where they were caught in an eddy behind a pair of fallen branches. Her last-rinsed large sheet had escaped as well, swelled open like a sail and, most likely because of its length, overcame the small irregularities and cross currents to go smoothly downstream with the flow. The second washerwoman, on the western bank, was sympathetic, yelled “I got you, sweetie,” and stepped in to retrieve those smaller items, while the first ran slipping and hopping distressed, a dozen yards downstream, past the third washerwoman, who laughed bitterly and could be moved no further, to get in front of the sheet, and she thanked Jesus that it caught itself squarely on the mouth of a large chain-link fish trap, so that the sheet was stretched long across the mouth of it, its lengths trailing in the water, and the flow of the water along the sheet was strong enough to pull the trap up, angling it up out of the water where it had been hidden.

The first washerwoman waded into the water to retrieve her sheet. Rytius watched her from the footbridge, and he appreciated that she didn’t go to pulling and yanking immediately. She paused for inspection, so that she could remove the sheet with care. The trap was a metallic skeleton of a box, a sieve, but the sheet around it changed the flow of water through it. The water flapped the sheet in a rhythm against the sides of the trap, and that rhythm was also the constriction and dilation of the flow of water into the body of the box, which modulated less and more the flow of water out of the square links on top, which was visible as a pattern of rising and falling deeper and shallower ripples out of them, on the surface of the water. Whereas the section of sheet against the mouth of the trap was also a screen against the flow of water into it, and this plus the angle of rise protected those surface ripples from the agitation of the river itself, though it did not shape them. It let them be seen. Finally, a miracle of desecration, one section of sheet hung no more than 3 or 4 inches over the top of the mouth of the trap, and the waters rose unpredictably periodically to flap it against the top of the trap, scattering and scrambling the ripples entirely into a chaos out of which they formed again. It was an accidental device of crackpot ingenuity, designed for something else entirely. Rytius wanted to sketch it, but he had neither paper nor pencil, and it was too wet anyway.

“Don’t come over here messing me up,” the third washerwoman warned her even as she passed, returning to her station. “Hey, you did it!” one fisherman yelled. “Pure luck,” from another. She stood discouraged over the pile of laundry that had fallen into the mud, and the second washerwoman yelled asking whether she wanted her to throw the smaller stuff across. The first washerwoman considered whether she could catch them in her already chilled hands, and she weighed the risk of them landing in the water or the mud. She considered walking across the footbridge, glancing quickly up at the crowd of men who had been mocking her, and so she crossed the river. The water had risen almost chest-high and it was a freezing rain, but she worked these waters daily, and she was well-insulated after all.