11. Castle Henderson

There had been no incident of any kind. The bed of the black truck was filled, and rents in coin and kind shifting heaved—canvas bags stuffed with envelopes of silver, gold and copper jangled against uneaten winter stores of potatoes and southern-bought grains, which would serve as starches for alms and cakes for Saint Patrick’s Day. Among the sacks of grain and money were carefully lain boxes of distilled spirits, their glass bottles separated by heavy paper shocks, rattling nonetheless, neck against uneven neck, because the boxes had not been properly fully filled. Ritius had long ago recognized a sort of rise and fall where rents were concerned. When he first began these duties, the fall in the quantity and value of the rents after the first autumn month would enrage him, driving him excessively to punish both debtors and those who offered moonshine instead of money. The knowledge that the people’s wealth was more like the seasons, and that one may as well reprimand the sea for waving, made him feel wise and merciful. He was no fool, though, and he still wouldn’t accept wine, cider, or beer. The quality is too various, and the temptations of the job had made it impossible to find sober, reliable inspectors to regulate the production of the entire universe of fermented alcoholic beverages.

◆ ◆ ◆

Ritius wished to speak with Prince Feelharmonica about more than the rise and fall of the rents. He had to wait outside the office, because Feelharmonica was meeting with the spy he had engaged to surveil his older brother to the south, Prince Koolkup of New Gunswick. According to Ritius, Feelharmonica was making a mountain out of a molehill, and the molehill was Koolkup’s management of his relationship with New York, regarding Staten Island. There remained one single bridge connecting Staten Island to New Jersey, and it was hard to overestimate its economic and political significance, as it was both an explicit condition of the peace between North New Jersey and New York, and the source of the only, though great and growing, import tax revenue Koolkup received, and his principality was the bulwark against the chaos of southern New Jersey. So he took frequent trips to New York, spoke most frequently with New York, and had business relations with many Staten Island merchants and factors and tradesmen and the like.

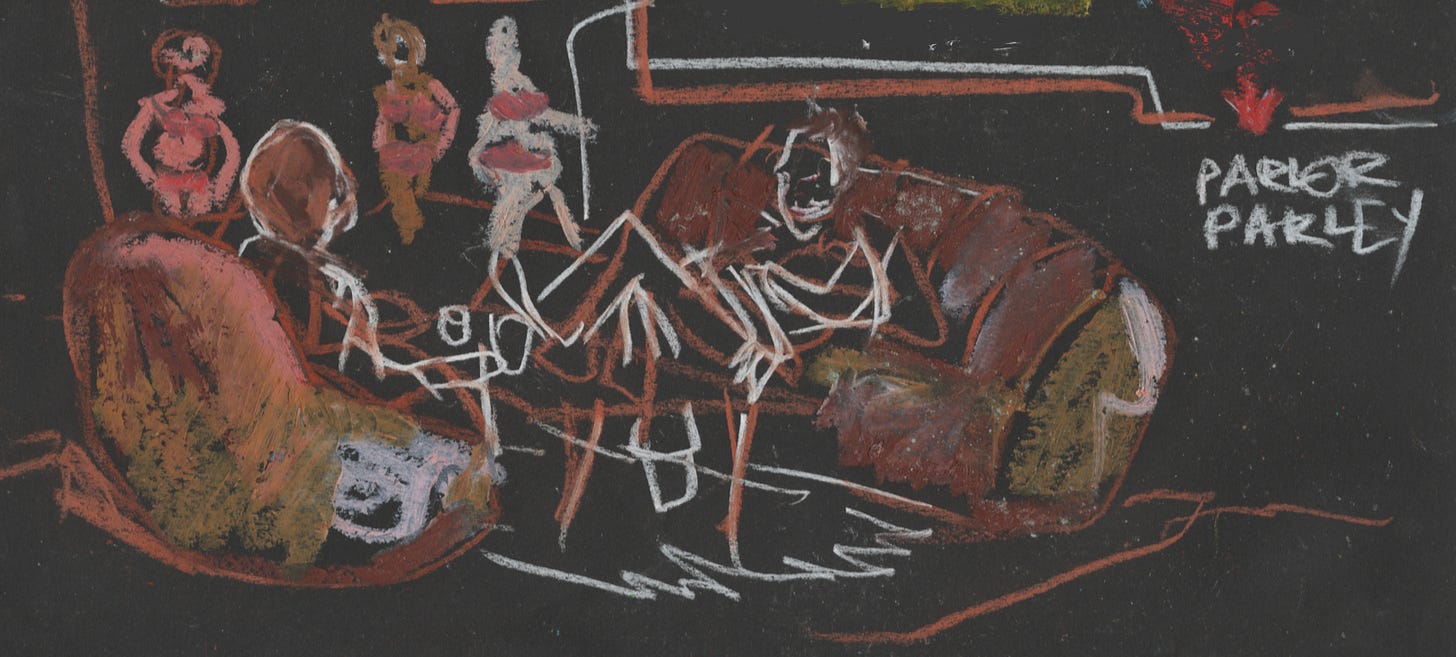

There were three concubines in Feelharmonica’s parlor. Sorrel, his favorite, dared to stay when Ritius entered. Ritius determined to ignore her entirely. Feelharmonica considered himself to be open-minded and liberal in his relations with his women, and Sorrel had grown comfortable in her role as a sort of secret streetwise counselor. Feelharmonica believed that he could use her while properly discounting her distorted partial perspective and any ill will she might harbor against him for her position. She was well compensated after all, and she did not desire to be his wife—he did not feel he needed one, yet—and she would not have desired children even if she were capable of it. Ritius had told him more than once that he relied too much on her, which is to say, at all. But Feelharmonica was proud to possess a woman of her intellectual acuity. He enjoyed her little games, and was confident that he had them well in hand. She was quite well placed, and had come to know everyone of any note. “I swear to you, Ritius, that Koolkup is going to be the ruin of our kingdom,” Feelharmonica pronounced, seating himself informally on the sofa. Sorrel took his side and curled and shifted her legs under herself like a cat. It was some small relief to Ritius that Feelharmonica dismissed her before she had gotten entirely comfortable. The prince enjoyed his little games as well.

Ritius took the club chair across from him and poured them both a bit of whisky.

“Can I be honest for a minute?” Ritius asked, while sliding the prince’s drink across.

“I don’t know,” Feelharmonica grinned. “Can you?” He took a sip and sucked his teeth.

“That so-called covenant? established something, but it surely wasn’t a kingdom.”

“Not this double-dug dirt again,” Feelharmonica groaned. “I’m about to start taking it the wrong way.”

“You have yet to dispute my logic?” Ritius felt that, as a soldier and as a servant, he had to reiterate his position. “This were a kingdom only had your father survived.”

The Covenant established a sovereignty of some sort under the name of New Ark, but it was really just a treaty, and no founding document. There was discussion neither of the sovereign’s border with southern New Jersey nor its administrative or executive structure, nor its inner divisions or succession policy. The only geographical discussion was the explicit confirmation that Staten Island indeed still belonged to New York. Prince Appall ignored all these questions of state. His only condition, spoken, was that New Ark, the middle portion of the sovereignty, would be primus inter pares.

“But still. You remain primo enterprise. So if there’s anyone in a position to finally found that kingdom? it remains you.”

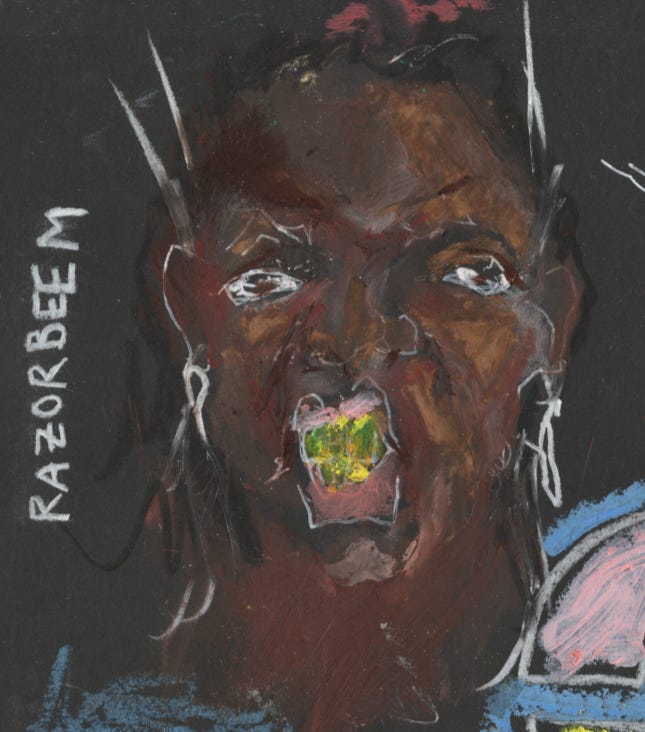

Feelharmonica glared at Ritius. He remembered when they met, long ago, in this, his father’s very house. Ritius was a bit older, months, and Feelharmonica and his younger brother (before he took the name Razorbeem) played with all the children of the house—his mother’s sisters’ daughters and his father’s wards, pages, and squires—and these two, Feelharmonica and Ritius, were boyhood friends for as long as Prince Appall would allow. Feelharmonica came of age, and he grew to learn his father’s callousness, particularly toward his very own self, as he, in his heart, abandoned his boyhood friend to his fate as his servant. His father died before teaching him the most salient method of converting pride and self-regard into a chrysalis of contempt, so that he might cope with such crippling isolation.

That frightful alchemy almost always entails the systematic abuse and humiliation of those one wishes to dominate, but only because at the end of such treatment, the dominated, now deprived of their dignity, cry out for further insult, and can in no way appear similar to oneself. For instance, there was nothing natural about the way in which the Coleman boys came to Castle Henderson, though such a thing might be expected, given the status and position of the people involved.

Fastes Coleman was a military leader, like his father before him, and his before him. He was Appall’s favorite of his father’s armorbearers, as it had been with Feelharmonica and Ritius. So, at the beginning of his reign, Appall appointed Fastes general of the legion he raised against the south, to establish and fortify his brother Boy at Trenton, where he would be a sort of marshal over the territory, and also necessarily to push the Gardeners back up against the Virginian Dominion, in hopes that the Gardeners would be crushed and die out, abandoned, exiled, and mercilessly extorted by the marauding paramilitaries of the long demobilized and disbanded Pennsylvania National Guard, who were more properly called Illadelphians then, rather than now, after discord and strife have split them apart; they remain what they were, only with smaller forces and that many more enemies.

Fastes performed his duties for 7 years.

Appall was and had always been generous to Fastes, his trusted general, calling him a friend. No one could recall Fastes ever trading upon his familiarity with the prince, and Fastes never made any attempt to challenge Appall publicly on any matter of state. It might be said that Fastes retreated too abruptly into private life. He and his new wife Lalala—a dressmaker originally from Roosevelt, Long Island—eloped and honeymooned the springtime with her people, conceiving their first child, the boy who named himself Rytius. By no accounts was Appall at all shaken by this. He spoke with no one about his friend, General Fastes, and in fact, Appall hosted a celebration for the newlyweds upon their return from Long Island.

Appall praised Lalala for her poise, because she was a common woman. He did not mention what no one failed to notice. Her beauty was such that a man would stop walking, talking and breathing just to watch her move across the room. Her body was thoroughbred perfection, and her eyes betrayed secret wonders of thought and feeling a man might do wicked things to know.

But Appall and Fastes embraced one another, laughed together, danced with one another’s wives, and generally played fools that evening. Appall had not yet hardened his heart against his old friend. Or perhaps he was practicing the duplicity that later served him so well.

He did bark Fastes whether it were a greater honor to have a prince attend a wedding, to have a prince host a wedding, or to have a prince miss a wedding. The outburst struck everyone silent. Even the piano player stopped. Fastes paused, smiled and barked that the last option is the best, because one can be sure that the prince, having missed one opportunity to show off, is sure to make an even grander display of generosity. The hall exploded in laughter, Appall actually fell off his chair, and when Fastes went to him, he also fell, and they tumbled down drunk, laughing.

Appall did not fail to govern, and early the next March, he again took up arms against rebels in the north, who began calling themselves Gardeners after those in the south. Appall raised a brigade, naming it after Saint Patrick, and its policy was to wipe these New Gardeners from the face of the earth or, failing that, to push them south of Trenton. The Gardeners, new or old, had no policy, because they had neither king nor prince nor ruler of any kind, but they are loosely bound by their ideas of liberty and justice. Their ideas and their flag are heirlooms, but they are like their forefathers who somehow never managed to live in the manner they preached. They, like their forefathers, are as poisonous as the snake they hold aloft, always carrying in their mouths a ready excuse for unfreedom, false imprisonment and injustice. But they were more than capable of bombing bridges and sabotaging dams as they fled southwest into the forests and swamps.

Appall soon required a team of builders, craftsmen and engineers of several kinds to inspect and to renovate the three dams near Paterson, and to restore the electrical power supply, if possible. The Passaic flows north for a while, from out of the swamps of County Morris, to the Little Falls dam near the Great Notch in the Achtung Mountains, and north still to the Great Falls dam at Paterson, just north of which the water turns south, toward the ocean again, to Dundee dam, near the town of Garfield, and thence the river runs down the plains to New Ark and the bay. All this territory was occupied by New Gardeners, and that team of highly skilled men, though under armed protection, suffered casualties sufficient to raise alarm, and so Appall commanded Fastes to take a small squadron to the Great Notch, while Fastes’s firstborn child was not yet three months old.

If a stream of southernbound refugees forms a river, Appall sent Fastes and his squadron swimming upstream, north along the western face of Orange Mountain. No one survived, and Appall took Lalala and her infant son into his home, where they lived under his protection. That December she bore him a son.

Perhaps a year after the birth of that second son, the boy who would name himself Ritius, Lalala fell ill with raving. She was found wandering Brookside, near House Coleman, half-naked, her face garishly painted, as though she were a sorceress or a clown or both, ranting about debt and recompense, not vacating the throne nor ever abandoning the castle but reinforcing the fastness, and Appall formed a bodyguard for her, and brought doctors to look after her health. She told visitors that she was the sovereign, and that Appall was not even a pretender but a worm eating around the edges of her seat, spoiling her place, biting and stinging her behind. He began to confine her to her rooms when appropriate, and then regularly, as a matter of course. After she overturned a heavily laden dinner table one evening, Appall began to consider her a danger to herself and others. When required, he did not hesitate to strap her down to her bed. Her guards became jailers, and soon she had no visitors save Appall, two nights a week, three weeks per month.

She never withered, but she threw herself out of her bedroom window one morning when her guard released her for breakfast. Appall’s associates had forgotten her, and he did not proclaim her death. There was no record of the younger child’s true paternity, and upon their official conscription into his service, the boys were simply considered orphan wards of the prince.

Feelharmonica trusted Ritius, all the more because he was so consistent, insistent, and persistent. Feelharmonica settled back into his sofa. “But you somehow don’t think Koolkup is a problem that needs to be solved.”

“I’m just asking questions,” Ritius said.

“Either way it needs to be solved.”

“Let me tell you a story. You remember your father’s policies regarding the northern principality. The expulsions and expropriations? sending thousands of New Gardeners streaming south? where they fire the hearts of the others with their tales of dispossession, to which their scars and missing limbs bear witness? Those nettlesome snakebearers, biting our ankles in the south?”

“Of course. Koolkup has done well with them. He has even reclaimed my uncle’s lands near Princeton.”

“Yes, he seems to have them and the Illadelphians firmly in hand.”

“You say ‘Illadelphians’ like they are one thing.”

“I know better. It is just a manner of speaking. We know what goes on in the south. I want that spoken. I want to talk to you about the north.”

“Proceed.”

“One of my oldest long ago boys, Balloony Louis, from Eo…He was with us in your father’s house for a while, but you probably don’t remember him. He moved north after the war, a couple years before Six Bridges. A born businessman, believe, he left his family and his respectable home to make a name for himself in Paramus…to establish an outpost up there for him and his partners, even before the seizures. After the expulsions, he petitioned your father for the right to operate several choice concerns. There was a furniture paint shop finishing goods for New York cabinetmakers, and there was a beer bottler and distributor. The latter was problematic, because a significant portion of the deliveries were to bodegas in Brooklyn. Getting back and forth across the bridge in a manner befitting a profit-making enterprise was impossible, as his trucks were robbed and his drivers were killed.

“He was relieved when your brother Prince Razorbeem took over administration of the northern principality. He expected support of a certain kind, but he did not receive it. Razorbeem finished his father’s work there, and since has concerned himself almost exclusively with management of the waters, the dams, and the power supply.

“Water and power are vital infrastructure, given safety and security. But the latter were not given, and my boy and his colleagues had been forced to fend for themselves, paying what they must to whom they must for security and safe passage. That, I’m sure you agree, is disgraceful.”

Feelharmonica didn’t respond.

“So Balloony went to speak with your brother Prince Razorbeem. He is prideful, and he balked at first, but my boy had brought other operators to testify as well, and Razorbeem began to understand that commerce itself is infrastructure, as are business relationships in general. He learned the lesson that you reproach your older brother for learning too well.”

Ritius paused to allow the prince to appreciate the symmetry. Feelharmonica gave him nothing and, stonefaced, cocked his head slightly.

“Those two princes, your older and younger brothers, in the absence of any new teaching, have come to learn that they must make their own separate peace with New York, given our historical entanglement.”

“My father wanted a new relationship with New York.”

“And he might have forged it had he lived. Meanwhile, to your north and to your south you have two separate relations, each a sprawling collage of compromise and convenience, mastered by no common vision.”

“Don’t think that I am blind to your concerns. I have spoken with both my brothers,” Feelharmonica stood and walked behind the sofa. “About this and more than you know.”

Ritius sat silently.

“Koolkup is preoccupied with the defense of our southern and western borders, it is true. We cannot minimize his efforts on our behalf,” Feelharmonica admitted. “But Razorbeem,” Feelharmonica paused. “He called me a warlord last time we talked,” Feelharmonica chuckled like a cough. “You believe the nerve of that little peasy-headed, stunted growth, platform shoe–wearing poseur? Anyway, when we talk, he reminds me that our kingdom rests upon but a single support and, like you, old friend, he repeats himself, saying that we have no power independent of New York, and that we live like mosquitoes, sucking the blood of those with whom we have nothing else to do. We can hardly increase our sucking power, because even our current position was purchased too dearly.”

“Neither of your brothers is a fool. But my story is not done. You and I are sitting here and we have understood and spoken the truth that each prince is forging his own policy with regards to New York. But we know only the one and not the other.”

Feelharmonica was surprised at the suddenness with which this new knowledge had taken shape, before his eyes, with his own participation. He was shaken by the sheer size of the hole it revealed in his understanding, struck by the fact that he had already known every fact required to understand, and humbled by how wisely his old friend and counselor had revealed it. He could not speak, but he swallowed and stood, still.

“Your brother Razorbeem took Balloony’s concerns to heart. He solicited bids for security services—I believe he met with Councilor Justice Boniface, given that she runs market security here, in New Ark proper. They were unable to come to terms, but your brother made armored vehicles available to certain merchants, and provides armed escort for a modest per diem.”

“OK, so he is behaving as he should,” Feelharmonica noted. “But how can he safely disperse so many men? Smallest lands, smallest numbers.”

“My friend answered me well when I asked him the same question. Your brother has his garrison between Paterson and Paramus, near the bend in the Passaic. He requires that merchants report there at the beginning of the week, one week before they require his escort, to preserve their place with a deposit of gold only. So, he was there, waiting in the lobby to see the administrator. The prince and his bodyguard crossed the hall and paused. They were not to be alone, because another group of men was rushing to join them. That second group were workmen of different sorts, tools and implements strapped to their belts like six guns. They exited the building and entered their vehicles outside, and it was a large caravan, with several armored passenger vehicles, more than two pickup trucks, and what struck my friend the most was the large armored tractor with an open trailerbed, on which was installed machinery unlike he had ever seen, and had only ever even heard of. It was some sort of large crane or wench.”

“It sounds like he was heading out to inspect the waterways.”

“That’s what I thought, too.”

“Well?”

“That’s also what my friend thought.”

“So?”

“All the vehicles were marked with the seal of the King of New York.”

Feelharmonica froze, trembling, and clutched the back of the sofa to steady himself. When he released it, he pursed his lips and walked back around to sit again with Ritius. Ritius let him gather himself, and sipped from his tumbler while waiting for his prince to speak.

“Now we know the shape of both relations.”

“We do, in general. But we do not know the price Razorbeem pays.”

“Let’s assume that it is too high.”

“Yes,” Ritius agreed.

“I guess you’re waiting for me to ask you for your counsel.”

“Yes.”

“You think I would shoot the messenger here.”

“No,” Ritius replied agreeably.

“I need to pull a tooth to get you to say something now? You’ve already spoken so freely, my friend.”

Ritius most definitely did not want to play diplomatic games, but he wanted to hear for himself the prince’s first utterances after this new knowledge. He continued.

“I have been your man for years. I have fought for you. I have guarded your life with my own. I have had the honor of serving as one of your counselors. You know me.” Ritius set his glass down and leaned forward over the table. “You say that I repeat myself, but I have also repeated my conviction that only you can establish the kingdom your father failed to found. You can. But you are doing nothing to that end while your brothers work toward even others. Even with your privilege as primo enterprise, you need a plan and you need your brothers to agree to what you propose. What exactly are you doing?”

Ritius realized that Feelharmonica was waiting for him to finish, and that he was no longer listening. Ritius sat back, rested his hands on his knees, and concluded by trying to state matters as forcefully as he could.

“To me, it looks like you are attacking some of your most beloved citizens, and spending time and money that you cannot afford, in order to drag building materials up the face of Orange Mountain, to build a museum, of all things, to mock a world long dead.”

Feelharmonica nodded conservatively, in the manner indicating that one has listened carefully. He took a deep breath and a swallow of his liquor, and a considerate silence filled the parlor.

“Are you feeling sentimental about your brother?” Feelharmonica asked coldly, no expression on his face. Ritius knew that he had upset and alarmed Feelharmonica with his analysis, and that Feelharmonica might be seeking to turn the tables, to make himself feel better by belittling or mocking Ritius. His affectlessness could be convenient cover. It could also be sincere. Ritius chose his words carefully.

“It’s not personal. I believe the policy to be misguided.”

The prince blinked, and seemed to settle himself. “Do you know about this game they play?”

“I know something about it,” Ritius admitted. “I’ve never seen it played.”

“Who chooses the topics presented?”

“No one. The presenter. It’s not directed.”

“Are the presentations approved?”

“No.”

“Is there any review of any kind?”

“No. Well, the group applauds or decries the presentation. The matter is decided there.”

“Is this true for both factions?”

Ritius realized that he had only been answering for his brother’s side. “Now that you mention it, there are differences between the two factions. The one is as I have described, and the other is different.”

“The faction decides as a matter of policy the area of research and presentation, from what I understand,” Feelharmonica said.

“Yes, they identify an area ripe for what they call exclusion, and they work for weeks, months, and sometimes years to conclude such a project.”

“The whole group undertakes a project?”

“There are teams, I gather.”

“Who decides to undertake a project?”

“I am not sure how they decide, but the leader of that faction is one of the original recordkeepers, Tellem Ralph.”

“If there are teams, then there is a division of labor, which means there is some decisionmaking process, which means there is a decider.”

“I think that must be the case.”

“What can be the result of such a project? Do they produce documents? Are their findings presented in ‘game’ form?”

“The research itself fills rooms, but the result is a relatively small document outlining the result. They compile lists of references and the like.”

“But the result is usually some sort of yes or no thing, right? A decision whether this or that could possibly have happened?”

“Exactly right. They comb through libraries, archives, artifacts, documents of any and every sort in order to produce history.”

“But it’s quite the opposite, isn’t it? They eliminate possibilities.”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“Another way to put it is that they remove controversy.”

“I suppose one could put it that way,” Ritius had to agree. The two men shared a silence. “But the price is a whole mess of martyrs.”

“It’s all to the glory and power of our kingdom…to be. You can’t put a price on that.”