16. Reason

There is always a place for reason but it is not very large. In fact, it is cramped and uncomfortable.

Reason has allies only when it does not need them, or when they are throwing it a surprise party, having already vanquished its foes. If reason confronts its enemies alone, it has already lost.

So Rytius, awakened by the sound of hail pellets against the window, began his day wondering again how to deal with his brother. Rytius believed that even if his brother were strictly business, Ritius would readily answer any questions Rytius had, and he had plenty. Like, for instance, what did the prince think he was doing with this tower? He reminded himself not to forget the bit about cash compensation. It would be useful to know what the prince thought about recordkeeping in general. Would the tower be like a large record store, in which listeners and readers could gather, discuss, borrow materials, deposit materials, help with indexing and collation? Floweria had asked who would staff the tower. Would there be fees or restrictions? Would it be open to the public? Would contributing recordkeepers retain special privileges or rights of access? What about sensitive materials? What about protection from theft? What about storage? Rytius had not heard from anyone about the prince reaching out for advice on how to store books, magazines, tapes, films… Heat and humidity require caution even where mere trash is concerned, let alone the concrete artifacts of the history of human thought and expression.

Rytius was turning these questions over in his mind and still had not decided how to put them by the time he heard a truck outside, as closely as anyone could expect to 9 am. From the side window of the kitchen, Rytius saw his brother approach the door, stop and then turn his head to look directly at him. He smiled, and so did Rytius, lowering his rifle.

“So is there some procedure we should follow here?”

“Nothing special. I don’t need to get every single title today, just see what you have, generally,” Ritius answered easily, smiling gently, as though to communicate his willingness to communicate.

Rytius’s normal suspicion where his brother was concerned was surpassed here, and he felt anger rising in his breast, because Ritius had enough sense to know that anyone spending hours and days and years of their lives sifting for no pay through the debris of the world gone by would have everything tabulated, dated, related, and, where possible, replicated. Rytius’s anger was coupled with a confusion as to what purpose Ritius would expect such a pretense to serve. Perhaps Ritius was trying to catch Rytius retaining or withholding items of special interest. And that would be an insult, because Ritius also knew that Rytius would be loath to hide his rebellion were he so inclined. These things are matters of honor, and both had taken the same lessons, together.

So rather than continue trying to figure his brother’s angle, he decided to obliterate the issue with weapon he had at hand. He handed his brother an accordion folder and considered whether he should kick his brother out after handing it over. “Here’s the full, up-to-date inventory.”

“The map is not the territory,” Ritius said, as he took it. His gentle smile slipped away and his face took on the look of a man with regrets. Rytius’s confusion deepened, and he wondered whether he had misunderstood, and decided that it didn’t matter because his anger remained.

“You know what I mean. And I taught you that anyway,” Rytius said sharply, turning away. He weighed his obligations to his colleagues and himself against his unwillingness to be degraded or insulted and accepted that there was nothing else he could do.

“That’s what I’m saying,” Ritius smiled again. “But, you know, I just wanted you to take me through.” Rytius heard the change in the tone of his brother’s voice, and he turned to look again. The look in his brother’s eyes, as though he were simultaneously requesting an embrace and apologizing for any misunderstanding and hopeful of a new start and hurt at this small administrative matter between them today, made him feel as though he had not seen his brother in years.

“Oh,” Rytius said, now realizing that there was indeed an ulterior motive to his brother’s ease of instruction, though it was neither degrading nor a snare, and that he had therefore been unjust to his brother in this particular matter. He did not speak but listened. As he prepared to accept his shame to himself, he wondered sadly whether and how his brother would turn this into some new manipulation.

“I haven’t been here in a long time, and I want to see how you’re…taking care of the…of our house.”

“Uh oh,” Rytius chuckled. “Yeah, I didn’t patch the roof before the snows this past fall.”

“Yeah, but you know what I mean. Listen, I know you spend a lot of time doing this work, and I know how important it is to you. I just want to see what you’ve been doing. What you’re proud of.”

If there was one thing Rytius knew, it was not to underestimate his brother, nor to let his guard down on anything not entirely within his own exclusive control. He could not allow his shame at having misunderstood what his brother claimed to be a legitimate interest in his life and work to distort his judgment. He decided to allow his brother freedom in this small range, granting him the benefit of the small doubt that he was not crafting another manipulation. Which made it more important that Rytius be clear about what was and was not under his own exclusive control. He reminded himself that Ritius worked for the prince. The prince set the policy. Ritius had to enforce it. Rytius was a victim of this policy. How would a guided tour around their ancestral home change any aspect of any of this? Regardless of his brother’s motivations in requesting it? Could it possibly matter what Ritius’s motivations were? Rytius decided that it could have no bearing on anything else, and that it was thereby acceptable, even though he would have preferred not to have to deal with his brother at all. He marveled at how appropriate it was that he himself bore all these responsibilities—forgiveness and accommodation of family, obligations to colleagues, maintenance of personal boundaries and preservation of a way back for estranged relatives—while his brother bore nor acknowledged any save loyalty to the prince.

“OK, brother. You have to admit your timing is atrocious.” His brother blundered about like a monster in the dark.

“Sometimes we are brought together by misfortune,” said Ritius.

“The same way we’re driven apart,” noted Rytius.

“Yeah, that’s right.”

Rytius had redecorated the master bedroom to match the era in which the home was built. He had womb and egg chairs, a thin, tufted leather couch on a frame of steel, a glass table, floating atop an asymmetrical wooden support. A phonograph rested atop a long wooden sideboard, a pair of stereo speakers hidden within it.

He kept his most prestigious artifacts and documents there: his televisions, film projectors, media players—things that might be traded. It’s not that the materials filling three of the four remaining bedrooms were less valuable, but that they were less likely to be held to be so. So the master bedroom contained many audio and video recordings, and many landmark historical periodical publications, and the glass display case contained trading cards, from Topps baseball to Wacky Packages and Garbage Pail Kids; there were such archaic board games as Candy Land, Hungry Hungry Hippos, Monopoly, Connect 4, Sorry!, and Scrabble; numerous varieties of Barbie, a full squad of GI Joes (including Cobra Commander and Storm Shadow), My Buddies and Teddies Ruxpin, and such WWF Wrestling Superstars as Hulk Hogan, Randy “Macho Man” Savage, Ric Flair, Junkyard Dog, Andre the Giant, and other heroes of the 1984–1986 seasons. He also had several Rubik’s cubes, a Lite-Brite, and a Simon Says from 1979.

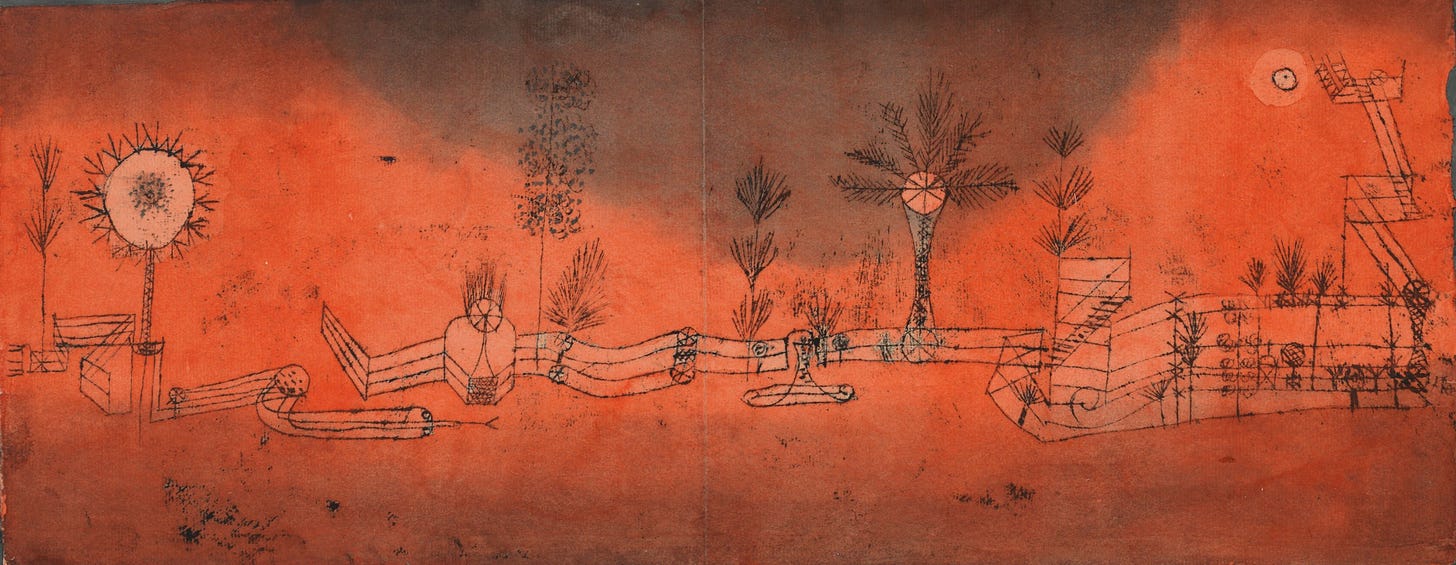

Ritius spent hardly any time there, but went into the adjoining room, the art room, which might have been his own bedroom had he or Rytius ever lived there when they were children. There were mass-market West African goddesses, 1930s movie-poster silkscreens, jade Buddhas and bronze trimurtis, impressionist and high-modern prints, many smallish watercolors and oils by Klee, Grosz, Picasso, Bearden, Klimt, De Lempicka, Lawrence, and others, and Ritius lingered over the titles of the many, many books lining the ceiling-high shelves—Jaffé, De Stijl, 1917–1931; Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Toulouse Lautrec; Sandler, The Triumph of American Painting; Mark Antliff, Avant-Garde Fascism; Youngna Kim, 20th Century Korean Art; Allan Wingate, The Temples of Angkor; Camille Paglia, Sex, Art, and American Culture; Wieland Schmied, Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism of the Twenties—whereas the tables were covered with oversized picture books and museum catalogues with beautiful covers, vivid volumes on the lives and works of olden artists—Van Gogh: The Complete Life, Matisse on Art, The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book—and the movements with which they were affiliated, from the Ashcan School to Orphism and from Dada to something called Der Blaue Reiter.

They moved into the third room, devoted to the works in the social sciences, of which each seemed to believe that it belonged to one or another distinct field of inquiry, be it sociology, anthropology, political economy, economics, or political science.

“So, are they not distinct fields of inquiry?” his brother asked him.

“They use different tools to examine the same problem,” Rytius answered. “The problem was always wealth and therefore power, and who has it and who doesn’t.”

“Some things never change,” Ritius noted. “So, what do they say?”

“The olden ones? About power and wealth?” Rytius replied. “What do we say today?”

“That some have it and some don’t,” Ritius answered.

“Why?” Rytius asked.

“That’s just the way it is,” Ritius said, blinking.

“The olden ones started with reasons why that is the way it is, upon which they disagreed,” Rytius said. “So they said many different things. But different methods produce different answers, so the question was never honestly engaged in any case. The question was posed only during times of war or revolution, and most thinkers seem to have conspired to submerge it as soon as possible afterward.”

“That seems impossible or overstated. How could such a conspiracy occur?” Ritius asked.

“Behind the backs of the conspirators,” Rytius answered. “Advocates of this or that reason were able to hide behind a political-science methodology here, and pretend not to understand arguments from the econometricians, who pretended not to understand what political economists argued, while everyone ignored the historians, and on and on in circles forever. And so most came to agree with you, that there is no reason, their methods having precluded its finding.”

Ritius turned his head and his entire body sideways so that he could more easily scan a row of titles—Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations; Bukharin, Economic Theory of the Leisure Class; Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis; Lyn Marcus, Dialectical Economics; O’Connor, The Fiscal Crisis of the State; Marcus Noland, Avoiding the Apocalypse: The Future of the Two Koreas; Harold Robbins, Fictive Capital and Fictive Profit; Krooss and Blynn, A History of Financial Intermediaries; T.R. Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population; McCormack, The Emptiness of Japanese Affluence; Preobrazhensky, The New Economics; Benjamin Yang, Deng: A Political Biography; Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics. “I’ve not read as much as you, but it seems safe to say that olden politics was entirely about economics.”

“Theoretically, entirely,” Rytius agreed, and led them into the fourth room. “The only distinctions I respect are among the practitioners,” Rytius answered, waving at the wall of shelves to their left. “Political actors were quite a bit more forthright about their differences than the scholars.” Ritius took it in. Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Outcast: Trotsky: 1929–1940; Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Armed: Trotsky: 1921–1929; John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World; Jean Barrot and Denis Authier, La Gauche Communiste en Allemagne, 1918–1921; Facing Reality, Facing Reality; clr James, American Civilization; clr James, State Capitalism and World Revolution; Situationist International Anthology; Seymour Melman, The Permanent War Economy; Michel & Shakeed, The Complete Guide to a Successful Leveraged Buyout; Rudolf Hilferding, Das Finanzkapital I; James Scott, Seeing Like a State; Amadeo Bordiga, Proprietá e Capitale; Jane Jacobs, Dark Age Ahead; Susan Woodward, Socialist Unemployment; Tiffany, The Decline of American Steel; Marvin Harris, America Now; Marvin Harris, Why Nothing Works.

“The titles alone are an education,” Ritius acknowledged.

“Yes, but if there’s only one question, and if it is never clearly posed, then one can’t follow the debate per se. One is forced to investigate the history of the question itself,” Rytius answered.

“A higher level of abstraction,” Ritius agreed.

“Which is why a lot of the titles in here are philosophical texts,” Rytius concluded. There were rows and rows of books collecting the works of Hegel, Kant, Benjamin, Heidegger, Lukacs, and Adorno, and multiple translations and commentaries on them, and another entire shelf of the works of Marx and Engels and their many commentators, also in multiple languages. There were thousands of others, and Ritius seemed to be enjoying himself—Russell Jacoby, The Last Intellectuals; William James, Pragmatism: The Meaning of Truth; Gerard Helferich, Humboldt’s Cosmos; Marcus du Sautoy, The Music of the Primes; Jean Charon, Cosmology; Eli Maor, To Infinity and Beyond; Franz Boas, Race, Language and Culture; Joseph Campbell, The Mythic Image; David Lewis, We, The Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific.

Rytius let his brother explore. He forbade himself from speaking further and from hoping anything at all. Ritius stood straight, and appeared to have satisfied his curiosity.

“Have you read all these?” Ritius asked him.

“Of course not,” Rytius asked.

“Why not?” Ritius asked again.

“It’s mostly a matter of time, I suppose,” Rytius went on. “We… I… we can’t—everything is not equally accessible. Some of these works require a specific education, and it’s not clear how to get it. So I… we just do what we can, and try to build knowledge and understanding.”

“Perhaps if all the records were gathered together in one place,” Ritius started.

“The records being in the same place has nothing to do with anything,” Rytius interrupted, as rudely as possible. His brother had no reason to pretend, and yet his brother had indeed chosen to utter the prince’s oily lies, as though they might actually persuade Rytius. It was two insults wrapped in a betrayal, when the betrayal alone would have sufficed. “We recordkeepers still have to do the work to make sense of them. Does the prince plan to support our work?” Rytius discovered that he had been hoping after all, that his brother would treat him with respect while doing his destructive duty. That he did not conveyed the message that nothing said had mattered at all to Ritius. He had no reasons of his own, and was somehow satisfied to have made himself entirely the agent of a spiteful and lawless power.

“I believe maintenance and storage to be support,” Ritius said stonily, meeting his brother’s gaze. There was nothing else Rytius could do. There was nothing more that he could hope from his brother, and he feared that there was no way ever to communicate with him again.

“It’s theft,” Rytius said. He was chilled by the finality of the rupture between them. He did not care whether his brother felt the same.

“It is the prince’s lawful command,” Ritius replied.

“And if we protest?” Rytius asked, curious to know the shape of the cage. He suddenly remembered that he had not gotten to any of the list of questions he had promised to ask.

“How exactly? I don’t know what penalties the prince would impose, but you know the things that can happen.”

“I don’t know how we would protest,” Rytius continued. “People find ways to express their displeasure.”

“Brother, there’s no need to make this any more difficult than it has to be,” Ritius said. “Should I be concerned about you?” Ritius asked. He looked as though he might actually be concerned.

Rytius ignored him. “You’re talking about the dispossession of immeasurable wealth.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” Ritius said.

“We’ve devoted our lives to recordkeeping.”

“There are no proposed rules against recordkeeping.”

“You’re being obtuse.”

Ritius then chuckled like a slick child about to escape punishment on a technicality. “Perhaps you prefer a pillar of fire to a tower of records.”

Rytius’s face became a stone mask as his anger rose, and then he was ashamed at having identified the location of the nearest blade to hand, in his mind—the sixteenth-century rondel dagger in the art room—as Ritius vaguely threatened him. “It’s not like that, brother, but it could be.”

Ritius stood stock still. They were alone together in what should have been their childhood home. Rytius lived among the legends of their ancestors, and he felt himself to be new wine poured into the old skins of their family history, as though a new spirit would vivify the dust of their past, known and lost, and that he would re-embody the best of their bloodline. Ritius visited this home occasionally, to water their legacy with the blood of fresh battles and civic triumphs, feeling himself fully in the line, and wondering why his brother didn’t see this clearly. He had wanted nothing more than to follow in his brother’s footsteps, and it crushed him when his brother left the service. He never looked back. It was as though he had forgotten himself and their legacy entirely. As though perhaps with years of dedication to the prince they had sworn to serve with their lives for their lives he would or could show Rytius where he went wrong. Ritius never let himself think about nor wonder about his brother’s persistence and steadfastness in his new course of life. What would make a warrior stand so strongly against his own legacy? The history of his own blood? The glory of his own battles? What would make a warrior leave the battlefield? Abandon all glower?

There are secrets these warriors keep from themselves. When a man goes to move the line of ultimate concern, he is never certain of his judgment. This necessary uncertainty is the cost of living a spiritual life. That is why such ways of life emphasize discipline, which is a method to keep one’s soul safe, free of corruption, streamlined, unbound to anything other than the object of devotion. If the warrior has been disciplined, he can trust himself, and he can leap, knowing that he has not lost his way.

But warriors do lose their way. It is entirely a matter of discipline or, more precise, self-deception as to lapses in it. The conscience can be seared, the moral sense crazed, prayers can turn special pleadings, and instead of communion with the absolute, soundings of self-pity or self-aggrandizement. One constantly checks one’s object of devotion against one’s honor, but what if one’s sense of honor is distorted? This is why there are regal, aristocratic, chivalric, clerical, republican, and democratic traditions. They show us the best that has been thought and done in these ways of life. And they, too, are subject to history, which means that they too can be lost. When confused, the warrior should look closely at this, his born or bred sense of honor. Self-deception is the subtlest corruption.

Ritius believed in that moment both that his brother was a fool for having lost his way, and that his brother was confused, having lost his way. He was sad on one score and scornful on the other. And yet he was not inflamed on behalf of the prince here. He did not feel the power of the state behind him, here before the fire crackling in the den. He still loved his brother, and were he quite a bit less serious a person, it would have been the perfect time for him to pat himself on the back, gratified that he himself was proving to be more mature than his own big brother. But he knew that Rytius felt himself in the service of principles greater than princes. If the world itself had not convinced Rytius of his error, what remained for Ritius to do? No, he had decided long before never to beat his head against that particular wall. And they shared quite a bit in common anyway. He had always admired Rytius for being so consistent, persistent, and insistent.

“Never change, brother,” Ritius told Rytius.

“OK,” Rytius answered. He was determined to be responsible to his colleagues, to ask their questions, and he therefore continued to speak with his brother. “I still want to know what this is all about. Why can’t we just keep doing what we’ve been doing? If Feelharmonica wants to get involved with recordkeeping, he could give us a building, or fund our work.”

“How would you like to tell him your concerns yourself?”

“If I wanted to do that, I would have done it already. I’m not going to sit in a room with that scoundrel and pretend to negotiate my own dispossession, or that of the others.”

“Would you do so in public?”

“It’s a public issue,” Rytius noted. “Yes.”

Ritius considered the range of options available to him. “The prince’s council is set to meet this week Thursday. What about a public hearing with the council? It would be an opportunity for you to ask questions about the tower, and for the prince to answer them.”

Rytius was momentarily pleased to have something to present his colleagues, until he realized that this was no favor, but just an opportunity for his concerns to be swept under the rug after a token airing of grievances. But with all the recordkeepers and as many interested citizens as they could gather, it was a chance to declare open conflict, and in such a state, anything can happen. So he asked whether “Feelharmonica himself is going to be there?”

“It’s his council meeting,” Ritius said.

“I gather the prince has some knowledge of recordkeeping if he’s concerned about records,” Rytius ventured. “Does he know anything about our game?”

“Only the barest notion,” Ritius answered.

“I think a demonstration would be best,” Rytius said. “It would allow me to communicate our concerns more effectively. Form and content, you know.”

Ritius agreed, the brothers dapped, and Ritius departed.