Rytius Records (Substack Edition), Ch. 7.3d

Ch. 7.3: The Comedy Games: Anamnesis, Meno, and Somnium Scipionis

7.3 The Comedy Games

Anamnesis, Meno & Somnium Scipionis

June 21, 2132

Wascal stood in a white toga behind a table in front of the bay window on the first floor of his record store, with the curtains drawn, so that the room was only electricly lumined. Kloz had a drum kit set up just inside the large parlor, next to the refreshments, which were entirely vegetarian. Wascal had platters of celery, snap peas, carrots, pitas, and hummus; tahini, chili sauces, olives, and multiple pickles, from cucumbers and radishes to red onions and cauliflower. There were solid blocks of ice for water (that he distilled himself with an ingenious solar-powered system of pipes and bottles), juices fruit and vegetable, and ciders hard and soft.

He held up a rectangular wood frame, perhaps 2′ × 10′′, into which was pinned a rectangle of rough jute burlap, which was dyed black. The burlap fabric flopped out past the edges of the frame, because it was only held to the frame in the corners. One could see each thread of the quite coarse cloth’s warp and woof. He laid the frame on the table, and then he painted a bright, glittery white stick figure on it. The contrast was sufficient to cause the figure to shimmer against its ground.

“Thanks GJ, Sugarpie, for the materials,” he said, nodding in their direction. “I want to start with this picture,” he said, holding it up. “Let’s say this is somebody listening to music.”

“If you say so,” said Carnation, chuckling at Wascal’s crude drawing.

“Where’s the boom box?”

“Can we get a drum at least?”

Wascal grinned and motioned toward the back of the room. “Kloz? You heard.” Kloz began a slow and steady kick on the bass drum.

He went on. “Before the war of Actium in 32 BCE brought an end to the Roman Republic, there was a general named Publius Cornelius Scipio, probably the noblest noble in human history. That’s the man who defeated Hannibal at Carthage in 202 BCE, and he became known as Scipio Africanus.”

He had the group’s attention then, and they were eager for him to rise to the challenge he appeared to be setting himself.

“The people loved this man: both his soldiers and the plebians. He was a land reformer, and made sure that his soldiers received some upon retirement. We don’t know what the proletarians thought, but they probably followed the plebians. He could have declared himself emperor after that victory over Hannibal, and a couple of other times after that. As you can imagine, the other aristocrats were jealous. Cato hated his guts.” Wascal touched the white paint of his skeletal auditor to see if it was dry. It was not.

“But he was a real republican. He didn’t want to be a dictator. He stayed a general, opened embassies, and kept winning battles. His enemies tried to bribe him to settle a battle, so that they could later impeach his victory as the fruit of corruption. They even tried to frame him for misappropriation of war plunder. I said misappropriation of war plunder. Cato brought bribery charges against him on the anniversary of his defeat of Hannibal, and Scipio wiped the floor with him in the Senate, and then led a mass march to church,” Wascal continued. “The temple of Jupiter, anyway.”

“Bless his heart,” said Carnation.

Wascal gestured Kloz, who increased the tempo.

“But do you see what I’m saying? Somehow, this man sidestepped his enemies’ every trick, every trap, every plot to destroy him and his reputation. With unerring accuracy, repeatedly, for years. How?”

“Good luck?” chuckled Tellem.

“God’s favor,” offered Fila.

“Fortuna!” yelled D-Man.

“The man was actually noble,” Wascal went on. “He loved the ladies, and so one time, his enemies tried to trick him into stirring up war again in a nearly pacified Carthaginian Iberia—Spain—by delivering him a beautiful woman they had captured in battle. They expected that he would use her as plundered war booty, but he didn’t. He investigated and found out that she was engaged to one of the potential belligerents, and he returned her to her fiancé, unransomed and unmolested.” Some of those gathered muttered appreciation.

“That was such rare behavior that artists painted the event for centuries after his death. The man was a legend of intellect and virtue, in his own time: a true gentleman and scholar. A Hellenophile, he spoke, read, and wrote Greek. He was a legendary general. He was obviously a great orator. He set fashion trends. Folks said he had second sight— premonitions in dreams and visions—and even his enemies believed that he communicated directly with the gods. He probably believed it, too.” Wascal held up his hand for Kloz to cease drumming.

Wascal paced ponderously, as though gathering his thoughts. He then gestured for Kloz to begin the beat again, original tempo, slowly, steadily, like an advancing Roman phalanx.

“So how does a man end up so different from those around him?” Wascal asked, checking whether his drawing was dry. “What do you think, Fila?”

“Er, I don’t know. I guess he just somehow had a different temperament,” Fila answered.

“He may have had better teachers,” offered D-Man.

“All the nobles had the same teachers, more or less,” Wascal said. “And how was he different, anyway?”

“He was just a better man,” said Carnation.

“But what do you mean by ‘better’?” Wascal asked.

“He wasn’t a jealous-hearted snake in the grass, for one,” she answered.

“Seems obvious he was smarter,” said Tellem.

“He was decent,” Vinilla offered.

“So he had a more developed moral sense?” asked Wascal.

“That’s a good way to put it,” said Carnation.

“What’s a moral sense?” asked Wascal. “I mean, what does a moral sense sense?”

“Just basic morality. Justice, goodness,” Carnation answered.

“So, something like virtue,” Wascal asked.

“That’s right,” she answered.

“Is there one virtue or are there many?”

“Hmm... there are many virtues,” Carnation answered.

“What is ‘virtue’, then?” Wascal asked.

“ ‘Virtue’ is being virtuous, doing virtuous things,” Carnation said.

“So doing virtue makes one virtuous.”

“Obviously.”

“So, how do you know any of those things, the many virtues, are virtuous?”

“Well, because... oh, I see,” Carnation said. “Because they’re virtuous.”

“Right. You can’t identify the thing that unites the virtues—virtue itself seems to slip away every time. We just recreated part of Meno, one of Plato’s Socratic dialogues. Socrates showed Meno that virtue can’t be taught, because if it could, no wise man would ever have a foolish child, and more people would be virtuous. After going through the whole thing, Socrates concludes that virtue is simply the way God’s gifts to the virtuous appear. Virtue is an instinct granted the eternal soul before birth, and virtuous action is the way it looks when that soul re-members its divine gifts. As for Tellem’s remark about intelligence, Plato has Socrates say ‘Nor is the instinct accompanied by reason, unless there may be supposed to be among statesmen any one who is also the educator of statesmen.’ So, not even Scipio could explain his fortuna, as D-Man put it.

“Now, appropriately, near the end of the Roman Republic, it’s greatest thinkers were struck with melancholy. They knew the age of such heroes was coming to an end. They knew themselves to be decadent. They had only to look in the mirror. One of those thinkers was Marcus Tullius Cicero, a philosopher and historian. He wrote a story lamenting the loss of such men, but recalling their immortality to his contemporaries.

“In that story, Scipio Aemilianus, the grandson of Scipio Africanus, is on the verge of defeating Carthage once and for all, finishing the job his grandfather started. Africanus was not his grandfather by blood, but by adoption. Anyway, Aemilianus has a dream in which his grandfather visits him and takes his soul on a tour of the galaxy, to show him how the revolutions of the sun, i.e., the measure of human historical reckonings, can hardly even be compared to the revolutions of the galaxy, let alone the scales that reckon eternity. It’s a shockingly visual demonstration, and probably one of the first illustrations of the lesson that we have to live our lives in accord with eternity, the only measure appropriate to the eternal immortal soul.

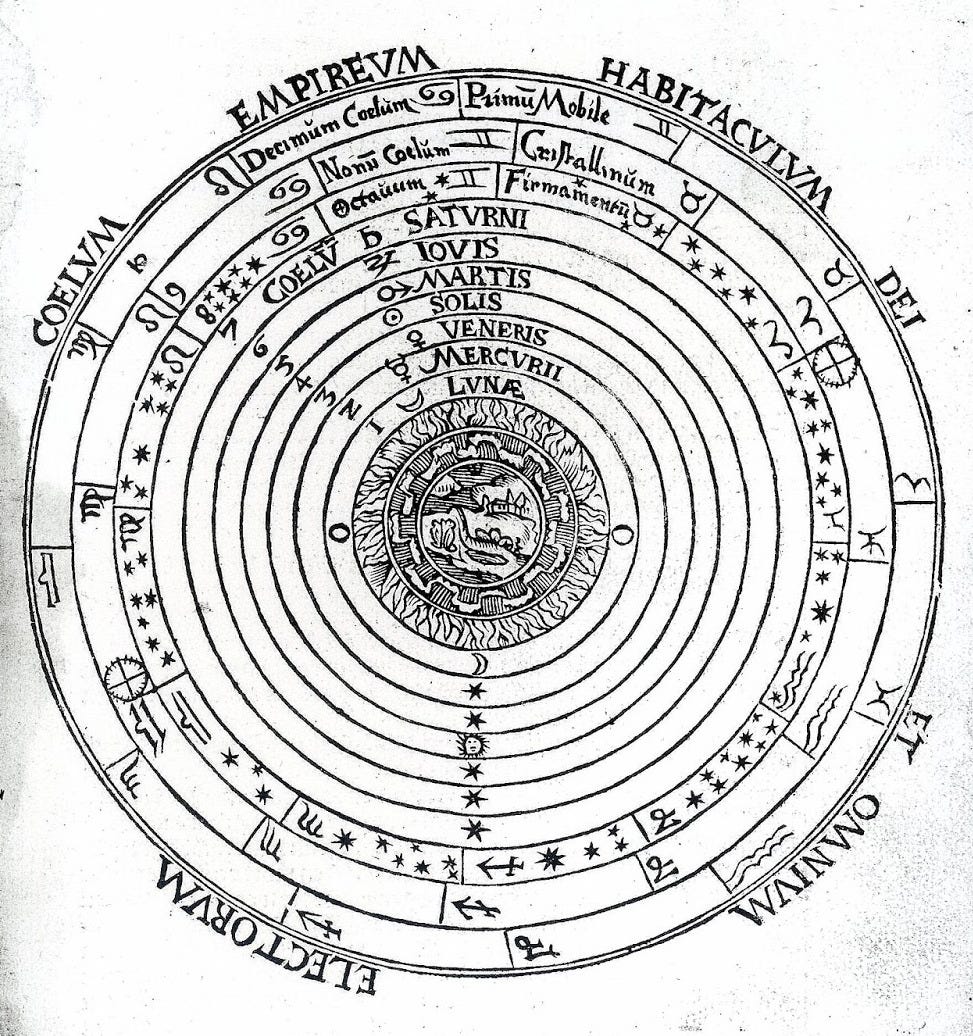

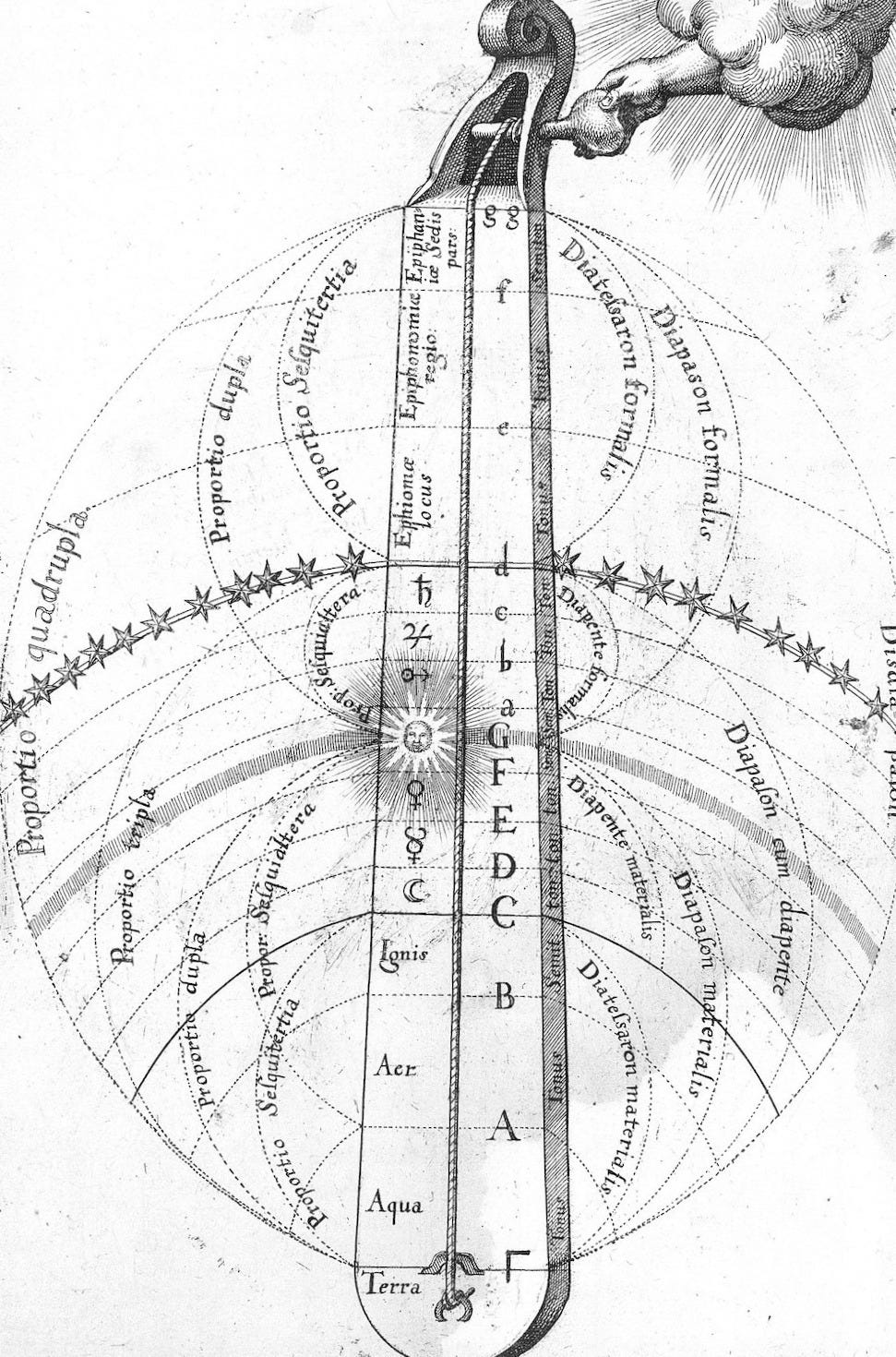

“Africanus also shows his grandson that the universe is arranged into concentric spheres of heavenly bodies, the outermost being the realm of the gods. Then the stars, and then Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sun, Venus, Mercury, Moon, and finally Earth, the lowest. They make sounds as they revolve in their unequal intervals, and that’s the harmony of the spheres, the musica universalis.” Kloz drummed several flourishes, filling more of the space between the steady beats of the bass drum.

“I want some of what they were on, OK?” said GJ in a stage whisper, while ribbing Tweety Bird.

“I don’t think you could handle it,” replied Tweety, in mock confidence.

“So we live in an actual octave, according to Cicero. Most people are deaf to the music of the universe because it’s so loud, but Cicero’s Africanus is saying that by turning our attention to our eternal souls, we can tune ourselves to these cosmic frequencies.”

Wascal paused and Kloz played a bit, rolling some rhythms into one another.

“Cicero wrote this story, and this whole book, De Re Publica, from within the Platonic tradition, and no one who read the story then doubted that it was a version of Plato’s own Myth of Er, in the Republic, where a man killed in battle visits the underworld, only to be resurrected, and to tell of all he found there. Plato used Er to illustrate Socrates’s idea of anamnesis, an anti-amnesia, un-forgetting, re-membering. The idea is basically that true knowledge is only ever recalled from the time before the soul chose whatever life it is in at the moment.”

“Oh, so all this depends on reincarnation, then?” asked Fila.

“Socrates’s anamnesis does, but not Cicero’s cosmic tuning,” answered Wascal. “That just depends on the immortality of the eternal soul. To the Greeks, reincarnation was just a corollary of the immortality of the eternal soul, like an implication.”

“You’re going to have to explain that,” said D-Man.

“They thought about it like this: if the soul is immortal and eternal, what does it do after death? It didn’t make sense to them that it would never enter life again, and just sort of hang out doing nothing in the universe. That would be somehow wasteful of cosmic soul stuff, and it would also lead to the afterlife being overcrowded. But I think you can tell that this is just some random cultural stuff. We don’t need reincarnation. The important thing is immortality and eternity.”

Fila and D-Man accepted this, for the moment, but Tellem did not.

“OK, let’s say we don’t need reincarnation to make Plato’s Socrates’s anamnesis work. But what kind of knowledge is he talking about?” Tellem asked.

“Right! Are these folks supposed to know things like the outcomes of sporting events?” asked D-Man.

“Or if it’s going to rain on your birthday party,” said Carnation. This line of questioning was important to those gathered at Wascal’s.

“Good question,” Wascal noted. “That came up in Meno, too. Plato meant formal knowledge—not data and information, contingent facts— but ideas, methods, and relationships. The moral sense, virtue, for instance, but even geometry. He calls the one knowledge and the other correct opinion. Data is correct opinion. Virtue is not exactly knowledge, as we have seen, but it is more like wisdom, a gift of the gods.”

“So what is the knowledge recalled, then?” Tellem asked again.

“In Meno, Socrates takes an uneducated slave boy through the process of recreating the Pythagorean theorem, just by asking him questions,” Wascal answered. “Socrates delivers no knowledge, but his questions check illogic. Socrates concludes that the boy must have known it already, and since he was never taught them, he must have learned them in a past life, because the soul is eternal.”

“Reincarnation again,” sighed Fila.

“That’s where he takes it, yes,” agreed Wascal. “The trauma of birth and the fact that souls bound for life have to take a drink from the river Lethe explains the amnesia. The questions guide the an-amnesia, according to Plato.”

“What a story,” GJ noted.

“But really, though,” Wascal went on. “That’s just cultural stuff. We don’t need to agree that every immortal soul drinks of oblivion before rebirth to agree with the shape of what he’s saying: sometimes knowledge seems to leap to mind without our having ‘learned’ anything at all. There is no effort, but the knowledge just appears and slides into place.”

Wascal gestured to Kloz, and his drumming contracted back to the martial thump of the bass drum. “With music there is time, i.e., rhythm, the foundation of the musical universe.” Wascal held up the fabric with the now-dry stick figure. “We all agree that this fabric has a rhythm? The warp and the woof are pretty regular.”

Everyone agreed.

“I like this fabric because it’s so coarse and rough that you can see the rhythm... ” Wascal held the frame up, presenting the figure to the gathering, and then he began pulling at a clump of woof threads on their left-hand side, which immediately distorted the figure’s head, giving it something of a squinting expression. “Rhythm changes are immediately perceived, and that perception immediately grants you the knowledge that something new is coming.” Kloz had complicated the rhythm as Wascal pulled the threads.

“Speaking of second sight, rhythm changes can tell us what’s coming, and sometimes we know the shape of the new thing, too.” Wascal tugged at several woof threads from the other side, a little lower, so that the figure shrugged a shoulder, and Kloz moved different parts of the rhythm to different pieces of the drum kit.

“It is important to clearly separate the moments of cognition and recognition, because they are not the same.” He pulled woof from the first side to pull the torso away from the shrugged shoulder. “That way we can see that the patterns according to which expectancy is evoked and either satisfied or frustrated can then become a new basis for communication.” Wascal threw the figure’s hip in the same direction as the shoulder. “But all this is lateral, linear. We’ve only been working in one dimension.” Wascal pulled warp threads at the top of the frame along the figure’s left side, lifting both its arm and bending its leg, and Kloz began to move a piece of the rhythm away from the rest, so that there were suddenly two rhythms. “Harmony has rhythm, too, and, likewise, the theory of harmonic tension and release relies on expectations that can be heightened, frustrated, satisfied, etc.” Wascal pulled warp threads down on the figure’s right side, and it looked like it would break itself dancing. “These are all modalities with which the artist can play to create new structures of feeling.

“I want to suggest to you that this is not only a man listening to music, but for Socrates, Plato, the Scipiones, Cicero, and many more for many years after them, it is also the eternal immortal soul astride, amid, aflight, amongst, the cosmos. The harmony of the spheres is not a metaphor, but the actual mechanism of anamnesis.” Wascal painted another stick figure, standing still, to the right of the first, already dancing.

“Recollection, re-membrance, takes place in a context, some sort of fabric, like this coarse weave, or a rhythm, or some web of concrete social relationships... You can see it right here. The first figure has been informed of the change in his universe, and it has directly affected his posture. He knows that something different is happening. It’s literally in his body, which is now distorted. He knows what his body used to be. That means he can communicate the change to his companion.” Wascal held up the frame, and methodically reversed each of the woof pulls that had distended the first body, thereby transmitting their inverse to the companion figure. Tweety Bird whistled approval and somebody clapped.

“Music communicates a structure of feeling by modifying it,” Wascal said. “Recollection itself—knowledge of how the fabric used to be—is the instrument that music plays in the mind of the listener. Music, as heard, is literally memory play: the skillful manipulation of the anamnetic capacity.

“The ridges, the knots, the snags and pulls in the web—this is how the soul reads itself, re-members itself, out of the texture of the fabric of the past, of which it was already the weaver anyway. And so, like Kloz taught us last week, modern music rediscovered its own ancient vocation: to mediate the relation of creative subjectivity to itself.”

Kloz crashed a cymbal, ending the music, and the two received more than a little applause. Wascal took an ironically noble bow, and the strap on his toga came aloose, and he fumbled to pull it back up—he was naked underneath except for his boxer shorts—and so the applause turned to goodhearted but embarrassed laughter, which quickly subsided.

“I love everything you’re doing here,” began Tellem. “But I have a question about the communication. The pulls on the up-down threads were not communicated across the fabric. They didn’t even touch the new figure.”

“You’re right. I guess that’s probably something that has to be communicated some other way—it can’t be read directly out of the web,” Wascal answered. “Not this one, anyway. But because the figures are vertical, most of the important stuff about the alignment of the parts of the bodies can be communicated via the woof.”

“So some of the information can be lost,” Sugarpie said, sadly.

“Absolutely,” answered Wascal. “As we know.”

“I tried to stay silent as long as I could last week,” Kloz added, “but because I played the music out of order, I had to reorder it chronologically. I could only do that, decisively, with words.”

“A whole dimension of the information can be lost,” Fila specified.

“That’s bad enough,” started Tellem. “But then we have to fall back on the lexical anyway.”

“Well, we’re not telepathic, either, but we can still communicate a whole lot before we start talking,” noted D-Man.

“Yeah, it’s not like the music is saying nothing just because it’s not saying everything,” Tweety Bird agreed. “But Wascal, what is that dimension? What is that one, the up-down axis, the.. . er.. . ”

“Warp,” said Sugarpie.

“Yes, the warp. What does that represent here?” Tweety Bird finished.

“I think it’s harmonies in music,” Wascal answered. “Because you can interpret that ‘vertical’ information with a different voicing, even if you have a written harmony. And you can make a whole different harmonization anyway. And it’s similar for anamnesis: there’s information that may not fit the idiosyncratic events of particular reincarnations of the eternal immortal soul. Like, individual lives won’t have the exact same shape, so ‘vertical’ information won’t always apply.”

“Literally miss me with your precise arm positions,” joked Carnation.

“Or unnecessary cultural baggage,” said Wascal.

“OK, but isn’t it obvious that we won’t be able to reverse engineer all the wrinkles and distortions for everything we want to know?” Tellem asked. “Why shouldn’t we just accept, for instance, that Billie Holiday is the one who speaks to us, and build from there? We might find firmer ground to stand on doing it that way, and it might make it easier for us to build bridges to the others.”

Fila answered Tellem. “But you know Billie is not firm ground. You’re just arbitrarily choosing a position out of an unreasoned prejudice. Why not just accept the actual problem you have, which is making sense of the range of possibilities?”

“God has blessed us to discover something so beautiful, so useful, so real to us, here, today, across such a dark and dismal abyss, and you’re ready to throw it away and call it prejudice?” Tellem responded. “If that’s what it is, then I just might be alright with that, and I doubt I’d be alone.”

“Well,” Carnation said, looking at Fila. “It’s better to have something that you can work with, something you can build on, than a whole bunch of questions you can’t ever hope to answer,” Tellem concluded.

Fila’s response has stood unchallenged since that very night. His response was that the subject performing judgment about beauty or effectiveness is subject to the same difficulties noted at the first step, when the subject first encounters the object of knowledge: the problem of how to tell the difference between the subject and the object, i.e., how to avoid bias, which requires conflict and controversy, and can’t possibly be simple recognition of knowledge from wherever or, more relevant, whenever it comes. That would go beyond Plato’s wildest fever memory dreams, to require that every individual human mind already contains all knowledge from all times, with no amnesia, and that would render history and therefore individual subjective activity meaningless. This object may require that method, and it is not that there must be no change in the subject, and it is not like there must be no history to mind, subject, or thought. Fila’s position never demanded, required, or postulated the immediate infinitude of the individual subject, just the eventual universality of subjective activity, i.e., reason—which must occur across individual lifespans because science is a social endeavor— and the eventual adequacy of the subject, i.e., the collective human subject, to the ultimate object, infinite knowledge. Which means we must now and always be quite jealous, on behalf of the object, of the space between us and it.

Fila hoped that the debate would turn toward questions of how individuals would or could participate in such a boundless wonder, but he concluded pointedly against any sort of reliance on recognition or remembrance where reason can still perform. We must not presume to be able to recognize knowledge from different places and times. Recognition may well be that of old prejudices or faulty knowledge, and so the principles derived would be those judged beautiful or effective by those with that prejudice or faulty knowledge. The so-called practical position pretends to avoid philosophical questions of subjectivity, mind and knowledge at one stage, demagogically dismissing them as concerns of abstract principle, while merely reintroducing those same philosophical problems later at the moment of judgment, where they are uglier and even more vulgar, begging arguments about the utility of this or that bit of learning in these or those terms while dancing on the head of a pin. And after that, well, things really get bad.

While positions have hardened, and there is little direct engagement anymore, that second controversy remained unresolved.

◆ ◆ ◆

In any case, when Fila was in the castle, Prince Appall had charged his own chancellery with the maintenance of the church registry, but upon his discharge that responsibility reverted back to Fila. Fila managed things fine the first two years after the war, but he started to slip after the growth of the new thing with Tellem. One fine afternoon in September 2133, the prince felt it necessary to gather some of his young wards— Rytius, Ritius, Balloony Louis, and Milkman Washington—arm them with swords, and send them to investigate and to correct matters at the offices of the church registry. Fila had failed to send in several months of records and accompanying revenues from collections. They were hardly more than boys eager to prove their mettle. Rytius is the one who kept it civilized, and he and a grateful Fila became friends. Fila was the big brother Rytius never had, and wished he could be.