A Short History of Hip Hop

How We Got Puff Daddy

Ice Cube’s “Summer Vacation,” Death Certificate (1991), was The Last Gangster Rap Song. Like, it was the end. There was nothing else to say. But that’s not how it works, is it?

No, it’s not. Madame La Terre and Monsieur Le Capital must dance their macabre dance, they must revivify the cadavers for which they are responsible, making marionette zombies and other varieties of colorful monster, also, of course, for hire and sale.

What had happened was that Dr. Dre, the DJ/producer from Ice Cube’s original group, N.W.A., created just the thing to assist the state in hijacking the hip-hop production process. Record labels and distribution companies had been content to act as merchants, i.e., merely to sell this strange black creativity, but…

The Golden Age

Hip hop is part of the American blues tradition, which was adapted from West African religions, and which therefore goes to the beginning of world history and the human conceptual apparatus. But for our story, let’s focus on what you might call signifying.

I’m talking about toasting, ranking, capping, etc. I’m talking about “Shine and the Titanic”—the old song from back then, when the boat sank—and I’m talking about

Muhammad Ali, who somehow tends to get left out of this history, and H. Rap Brown, and “Dolemite,” Rudy Ray Moore’s self-conscious pastiche of the whole tradition.

Somehow, out of the economic crisis opened during Vietnam—in which we still live, in which the pie is still shrinking, accompanied then by fire-insurance arson of apartment buildings; President Ford’s “Drop Dead” to New York’s request for fiscal assistance; the ethnic tensions among the black Americans, Puerto Ricans, and West Indians; the general foreclosure of the future, as dramatized in Saturday Night Fever; and the withdrawal of historical possibility that still marks this era—came new musics of unemployment, signified by a lack of players and instrumentation, and by their reliance on mechanical, cybernetic, or synthesized production: hip hop, soft rock, and electronica.

In that “golden age” of the current apocalypse, hip hop was whatever the performers wanted it to be, and that could be anything, as long as it was convincing.

The Silver Age

In 1986, something changed. Eric B. and Rakim came out with “Eric B. Is President” and “My Melody.” Rakim was doing something that hadn’t been done before. He took the superficial rhyme of toasting and signifying and made it actually, self-consciously, poetic, with metaphors, odd rhythms, internal rhymes, rhyming over the bar line, etc.

That was the end of the “old school,” and the beginning of the “new school.”

It took about two years for this to catch on and change the world, and open the “Silver Age,” the age of self-conscious stylistic exploration.

The aesthetic is now self-conscious, and the ethics of production are clear: no biting, absolute originality, supreme production (beats). The goal is to make the best hip hop album every time no matter what. That could be anything, and it had to be convincing, but the challenge is now historical: artists recognize that they are artists, and that they are competing against the established corpus of classics.

The silver age is everyone’s favorite: the flourishing of styles and the digging in crates, the secret loops, the new techniques, the illest delivery, etc. Here we have, for example, Special Ed, Big Daddy Kane, Gang Starr, N.W.A. of Straight Out of Compton, Kool G Rap, De La Soul, Tribe Called Quest, MC Lyte, Public Enemy, Chubb Rock, BDP, EPMD, Diamond D, Nas, Showbiz and AG, Nice and Smooth, MC Serch, MF Doom/Zev Love X, Cypress Hill of Cypress Hill, Fugees, Pharcyde, Leaders of the New School, Wu Tang Clan. There are also plenty of old-school MCs who kept thriving: Masta Ace, Biz Markie, LL Cool J, KRS-One, Rakim, among many others.

The Cloudy Lining

It was a new artform from a new sector of society: a suddenly downwardly mobile black proletariat. Black workers were left aside, pushed out, unemployed, fired first in 1973, hired back last with wage cuts in 1974, fired first again in 1979, hired back last with no union in 1984, fired first in 1989, never hired at a livable wage again. The government-subsidized crack-cocaine epidemic tore through the cities, demolishing neighborhoods and families already strained by poverty.

The previous generation had worked in auto and manufacturing, had made soul, r&b, and funk, and gave birth to the civil rights and black power movements, but politics of the sort that had seemed inevitably victorious as late as 1970 with Huey Newton’s release from prison had somehow already failed, and the whole working class was under assault.

Bereft of political organization, hip hop artists still had a lot to say. They tried to understand the world, and spoke to one another. Rap had been dialogic at least since 1984, when UTFO put out “Roxanne, Roxanne,” and Roxanne Shanté responded with “Roxanne’s Revenge.” Public Enemy had been engaged in media criticism and political provocation since 1988’s Nation of Millions, and so it was no surprise when KRS-One and X-Clan debated humanism versus Afrocentrism and black nationalism on Edutainment (1990), To the East, Blackwards (1990), and Sex and Violence (1992).

That’s self-directed, independent, high-quality conceptual debate, hitting the auto-reverse tape decks of millions of black youths across the country. 1990 is also the year Ice Cube went solo, left N.W.A. definitively, and put out AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, with production mostly by Public Enemy’s Bomb Squad. That album is the only reason anything called “gangster rap” continued to exist and retain any respect, because N.W.A.’s EP 100 Miles and Running (1990), and their second album Niggaz4Life (1991), were straight garbage.

The Merchants

In 1986 Aerosmith and Run DMC recorded “Walk This Way,” and music companies began to understand they could make money off of hip hop. They waded in slowly, but by 1988, they were fully on board with new-school artists, not making novelty tracks anymore, but selling the work of EPMD, Jungle Brothers, and Boogie Down Productions, and literally hundreds of others who would never get record deals today.

But hip hop had not shed its character as a music of dispossession, lemonade from sour lemons. It’s fatal weakness was that it was made of pieces of the past: a past that could be repossessed as easily as the future had been mortgaged.

In 1991 Gilbert O’Sullivan successfully sued Biz Markie, RIP, for using a sample from O’Sullivan’s 1971 hit “Alone Again (Naturally)” in Markie’s “Alone Again,” I Need a Haircut (1991). That decision, Grand Upright Music v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc., 780 F. Supp. 182 (SDNY, 1991), even opened rappers and producers to criminal prosecution for “stealing.” The basis of the entire artform was literally criminalized.

And thus began the “leveraged buyout,” rentier phase of the music industry, in which properties were broken down and sold as parts, tranches, slices. Squeezed. Black hip hop artists were the first victims, of course, new artists newly dispossessed, again, in a way that was impossible before they tried to save themselves from their original dispossession by recomposing their musical heritage!

The squeeze continued through the CD era, boy bands and girl groups, Napster and piracy lawsuits, 360 deals and “music is free,” and finally streaming and streaming company–created AI-generated tracks pulling revenue from popular playlists.

“Free Speech” and “Controversy”, 1989–1992

In 1989, 2 Live Crew released As Nasty As They Wanna Be, their biggest album, with “Me So Horny” using a sample from Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Broward County Sheriff Nick Navarro, on the strength of a County Circuit Court ruling, decided to enforce obscenity in record shops in and around Fort Lauderdale. Luke and them sued Navarro, and lost in district court, but they won in circuit court in Luke Records, Inc. v. Navarro, 960 F.2d 134 (11th Cir. 1992). Ice-T’s Body Count released “Cop Killer” on March 10, 1992, and senators, congressmen, and police unions nationwide sought to boycott Time Warner in retaliation for the album, Body Count. The Body Count controversy caused Time Warner to delay the Tommy Boy release of Paris’s album, Sleeping with the Enemy, because of the song “Bush Killa,” a revenge-assassination song about George H.W. Bush.

The LA Riots, April 1992

On April 29, 1992, Los Angeles erupted into riot from the acquittal of the four police officers who beat Rodney King nearly to death on videotape.

If actors working on behalf of the state—which includes government, business, and anyone else authorized to operate and maintain the machinery of exploitation—did not conspire to effect what happened next, there is no greater happy accident in the history of counterinsurgency.

Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg released “Deep Cover” on April 9, 1992, as part of the soundtrack to the classic movie of the same name. It played everywhere all that spring, and it was thematic, apparently of a piece with Paris and Body Count, but from the West Coast streets, like N.W.A. had been, and like Cube had been… And so they worked all through the rest of April and May, during and immediately after the riots, to produce Dr. Dre’s solo album.

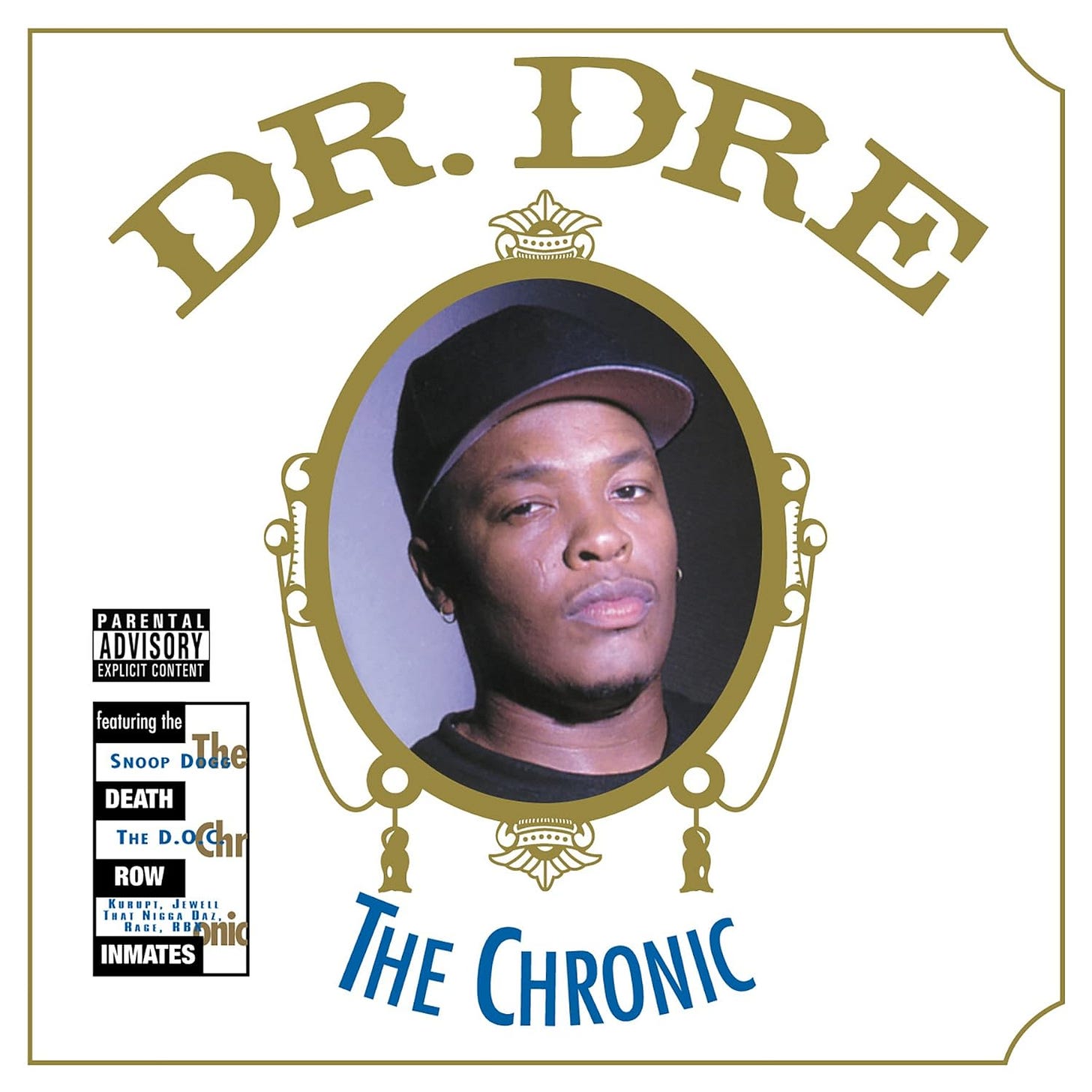

The Chronic, December 1992

And so The Chronic hit, and smoked out the whole room. Dr. Dre was back, and he and Snoop were just the men, at just the right time, to quicken the rotting corpse of West Coast “gangster,” “reality,” or “street” rap, with all the misogyny and backwardness of N.W.A.’s second and third albums, and so they did just that instead of doing anything to further the political dialogue the music had been developing in the years leading up to the riots.

Thus the state successfully re-marketed black degradation, not only to whites, but to blacks themselves, and immediately after the largest civil conflict in decades. Black audiences didn’t go for N.W.A.’s second and third efforts, but they went for The Chronic.

And then something happened that no one expected.

Doggystyle, November 1993

It sounds insane even to my ears today, but let me write this sentence: Dr. Dre bit off himself with Doggystyle. Yes, there is such a thing, and people knew it and spoke of it then. And the audience accepted this biting for the first time in the history of the music. And enough black hip hop artists acquiesced so that G-Funk could be born, yes, out of “the same old story, and the same old nigger stuff.”

That’s when the state knew that it could control not only the distribution but the conception and creation of the music, and they waged war on hip hop for the next 5 years, until 1997, when, I believe, they largely won, pushing the original independent creativity out of the mainstream.

Puff Daddy, 1997

Puff Daddy was the agent of that final consolidation. And so, finally, here I reprint an article I wrote in summer 1998, 26 years ago, on this very topic.

Rap Music Again, or, Focus on the Puff Daddy Family

I really want to get beyond the initially overwhelming irony of the fact that Puff Daddy and gang are flaunting ther realness through a medium which falsifies; I also want to get beyond the overwhelming initial irony of the fact that Puff Daddy and the gang are flaunting their wealth through the very medium which grants it, and must grant it before they can flaunt it.

What else is going on here?

Black people usually have some sort of subversive effect on American culture; rap these days is ultraconsumeroriented.

Rap music started with a critique of the economic system, i.e., The Message. Now the message has become one of success within the economic system, and a flaunting of the injustice that was originally criticized.

This is all too superficial. I need another level…

I refuse to sell out. That’s why I’m selling out. Or, lemme put it to you like this: in the absence of young black male role models, my life is incomplete without my daily dose of Puff Daddy. Meaning, if I can sell you this one piece of writing, you’ll buy another one just like it, and the more I talk about why it is good to get money and sell out—all controversial topics, especially when written from the pen of a writer, who is supposed to be advocating authenticity above all things—the more I titillate your nerves, and give you some new shit, some wholeothalevel shit, some next shit.

So, I am being really real by being really fake for a minute. Like Puff Daddy.

Then I can write some really next shit.

Unless my heart is hardened in the meanwhile by the contempt I feel for my audience, the source of my hoped-for wealth and freedom to write what I really want. Like Puff Daddy.

What else can you feel when you are flaunting your money to those responsible for your getting it? What else can you feel when you know that the only thing that keeps you in hightop Nikes is their desire to to be like you, and the gap between their reality and their desires? You know that if you really succeed, you can’t help but go farther, ’cause success for you means that people are spending their money on your shit, or studio time, when they should be paying the rent. And eventually, the hope that you started out with, the hope that you started selling, that you would be rich one day, becomes false hope because it becomes reality. But you can’t stop saying what you have been saying, because that is what made you rich! So, with rap artists, this wishful thinking—that if I sell out now, I can get over later, and really be real—never ends.

Niggas don’t learn.

But anyway, I’m selling out this time. And the next time. And a little bit after that. ’Cause I’m not writing about being rich. I’m writing about being broke and why I’m writing about being broke. To get rich. My hope can never die. My hope can never falsify.

After I get over on you fools, I’ma go to France like Baldwin, and write some really far out shit. Or Germany and start speaking Deutschmacks and Cadillacs.

Niggas don’t learn.

Puff Daddy makes music that acknowledges the master of art today: money alone controls. It truly is all about the benjamins.

To cover this cruelty, Puffy keeps it all in The Family. As if domestic abuse were not abuse. His “family” makes stars of all its siblings, and while we are not privy to the spats that certainly must take place, we can be assured of the internal strife in this family by Puffy’s overcompensatory proclamations of love, love, love.